Electric Don’t Vehicles Have to Be Expensive

When I bought my ID.4 cost was one of my biggest concerns, along with range and charging. I found a solution to my woes by leasing a car that offered free charging at Electrify America for 3 years. But that was hard to find.

I’ll save the conversation on the dysfunction of Electrify America chargers for another time. But my choice means that I save money while also not investing in a car that will be overshadowed as range expands over the next few years.

In a recent survey, more than half of Americans who don’t yet own electric cars said they were interested in buying one. But 64% said cost was a significant barrier.

As with any newer technology, electric vehicles can be expensive. But, they don’t have to be. BYD, the car brand the overtook Tesla as the largest EV seller which sells an EV that can go 250 miles on a charge for $12,000 isn’t available in the U.S.

An EV’s average price in the U.S. for 2023 was around $60,000. With U.S. interest rates at a two-decade high, the price tag for the average American car shopper is prohibitive.

Fortunately costs in the U.S. are coming down. As my former colleagues at NRDC note, EVs cost less than gas cars in the long run.

According to data from Cox Automotive (parent company of Kelley Blue Book), the average price paid for a new EV has fallen significantly—in September 2023, it came down by $14,300 over the prior year. This amounted to a cost of just $2,800 more than the average paid for a new gas-powered vehicle.

The majority of an electric vehicle’s costs come from the lithium-ion battery, and the costs of those batteries have declined 89 percent between 2008 and 2022. In addition to the advances in technology, incentives and tax credits have also greatly contributed to the downward cost trends of EVs. The other benefit is that maintenance costs are lower, with fewer moving parts.

Will Tax Credits and Incentives Help?

You can mitigate some of that cost by making use of tax incentives, which can shave thousands off an EV’s price tag. The federal EV tax credit offers up to $7,500 for new EVs and, for the first time, $4,000 for used EVs, too, for eligible buyers and EVs.

In addition, new rules from U.S. Department of the Treasury will soon allow participating auto dealers to provide the tax credit directly to consumers at the point of sale, making savings more immediate.

However, tariffs from the Biden administration make it unlikely that those cheaper Chinese EVs will be sold in the U.S. anytime soon. In parts of the developing world, where low-cost Chinese EVs are on the market, the share of electric vehicles on the road is quickly growing.

In Thailand, for example, one out of every 10 new car purchases is electric. In China, intense competition has led to more innovation. Some companies offer battery-swapping, so drivers don’t have to wait to charge their car.

Batteries keep getting smaller, lighter, and more powerful. With smaller batteries, there’s more space for storage or legroom.

Even with a federal subsidy of $7,500 towards the purchase price of an EV (made in the U.S.), many consumers still find gasoline and hybrid vehicles more affordable. For example, Toyota and Honda, who both only offer one EV each at present, both recorded substantial increases in sales in the U.S. of their hybrid vehicles, with Toyota up 16% and Honda up 32% on last year.

How Does the Charging Source Impact Cost?

If you are lucky enough to get the same Electrify America deal that I did, take it! When I go over my free 30 minute charge period, I notice the high costs of powering my car.

Charging at home is no different. Here in California, our utility, PGE keeps hiking rates, making the cost of charging higher.

Luckily EVs are 2.6 to 4.8 times more efficient at traveling a mile compared to a gasoline internal combustion engine, according to real world data collected by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

For an EV, efficiency is measured by how many kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity it consumes per 100 miles—similar to a gas-powered car’s miles-per-gallon stat. (A lower kWh/100 miles rate is better.)

A 2020 study broke down the lifetime fuel costs of battery-powered EVs versus internal combustion engine cars state by state.

EV owners in Washington State, for example, can save as much as $14,480 over the life of their vehicle—the highest margin in the country. On the other end of the spectrum is Hawaii, where going electric could ultimately cost $2,494 more over 15 years.

To get a rough estimate of your own charging costs, multiply an EV’s kilowatt-hour (kWh/100) mileage rate by your electricity rate (measured in cents per kWh), which you can find on your monthly bill. This will give you the electricity costs per 100 miles driven.

After figuring in the number of miles you typically drive in a month, you’ll be able to see how much your electric bill may go up.

So, What’s the Overall Cost?

You can figure out your savings estimate by adding together the up-front costs of your specific model (minus tax rebates) and then ongoing costs. (The DOE has created a calculator to help with this task.)

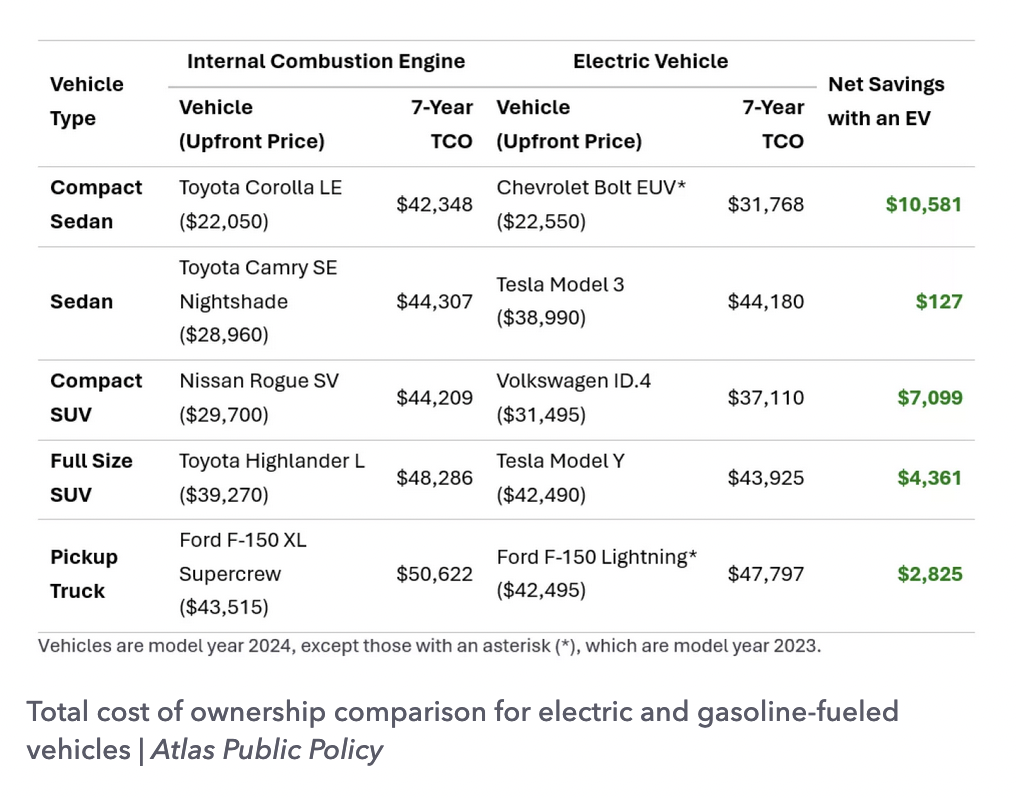

A study from Atlas Public Policy, conducted on behalf of NRDC, showed that for every major type of vehicle, owning an EV will save car owners money over a seven-year span, the average amount of time a driver keeps a new vehicle.