6 Myths About Sustainable Air Travel

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, I remember climbing to the top of a hill overlooking the San Francisco Airport and hearing silence. For the first time in the 8 years I lived here, the tarmac was still and the air free of planes. I thought, wow, it’s unbelievable we can put a halt to flying so quickly - and deep inside thought this was the chance to make a dent in the climate problem.

Fast forward to 2024, and flights now exceed pre-pandemic levels at over 40 million flights a year. That’s alot of peanuts and cookies! Between 1990 and 2019, both passenger and freight demand has approximately quadrupled.

Worldwide, aviation accounts for 2.5% of all carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and 12% of all CO2 emissions from transportation. A single long-haul flight can create more carbon emissions in a few hours than the average person in 56 different countries will generate in an entire year.

Myth #1: Airlines Have Not Reduced Energy Use

Since the 1990s flying has become more than twice as energy efficient. Traveling one passenger-kilometer in 1990 used 2.9 megajoules (MJ) of energy. By 2019, this had more than halved to 1.3 MJ. This efficiency has come from improved design and technology, larger planes that can carry more passengers, and a higher ‘passenger load factor’. Empty seats are less common than in the past.

The carbon intensity of that fuel — how much CO2 is emitted per unit — has not changed at all. We used standard jet fuel in 1990 and are using the same stuff today. Therein lies the challenge in taking a bite out of carbon emissions.

Myth #2: It Doesn’t Matter How Long Your Flight Is

When people think about going away for vacation, they often think of flying to a faraway land. However, long-distance air travel has a large environmental impact. Atmosfair has created an index for Airlines to report on all things emissions.

The study found that a long flight creates more emissions than an entire year of a single person’s food, energy, and basic transportation output.

However, in terms of fuel efficiency, as every plane has to take off, climb to a certain altitude, and land, medium-haul flights are more efficient than short-haul and long-haul. This study also shows that there are two factors that have the largest effect on reducing carbon dioxide emissions. These are the type of aircraft and the passenger occupancy.

Medium- and long-haul flights are the greatest culprits, accounting for 73% of aviation’s carbon emissions. According to the Aviation Environment Federation, UK nonprofit group that monitors aviation’s environmental impact, a return flight from London to Bangkok can produce more emissions than you’d save by following a vegan diet for a year.

Myth #3: Sustainable Aviation Fuels Don’t Impact the Environment

November 2024 marked a milestone in the field of aviation. Virgin Atlantic's Flight100, a Boeing 787, embarked on the world's first transatlantic flight from London to New York powered entirely by biofuel – fuel derived from organic matter rather than fossil fuels.

The fuel, known in the industry as Sustainable Aviation fuel (SAF), is derived from renewable or recycled waste such as corn grain, oil seeds, algae, other fats, oils, and greases, agricultural residues and more. It boasts substantially fewer carbon emissions — up to 70 percent less than traditional jet fuel. SAF is an alternative fuel made from non-petroleum feedstocks that reduces emissions from air transportation. SAF can be blended at different levels with limits between 10% and 50%, depending on the feedstock and how the fuel is produced. According to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), over 360,000 commercial flights have used SAF at 46 different airports largely concentrated in the United States and Europe.

An estimated 1 billion dry tons of biomass can be collected sustainably each year in the United States, enough to produce 50–60 billion gallons of low-carbon biofuels. These resources include:

Corn grain

Oil seeds

Algae

Other fats, oils, and greases

Agricultural residues

Forestry residues

Wood mill waste

Municipal solid waste streams

Wet wastes (manures, wastewater treatment sludge)

Dedicated energy crops.

Many scientists and international regulatory bodies have concluded that growing crops to make aviation fuel does not reduce emissions on a full lifecycle basis (from crop production through to processing and consumption). To meet the needs of the aviation industry, forests and grasslands would have to be converted, which releases stored carbon.

Sustainable aviation fuels are also inefficient - 1.7 gallons of corn ethanol are needed to make 1 gallon of sustainable aviation fuel. When accounting for total emissions, including loss of land, production emissions and loss of soil organic carbon due to tillage, the impact of using ethanol would be as high as 782 MtCO2. This represents a net increase in emissions of approximately 340 Mt when compared to burning the same amount of petroleum-based jet fuel, equivalent to the emissions from 75 million gas-powered passenger vehicles.

Myth #4: Using Hydrogen in Airplanes is Unsafe

We might think of the Hindenburg when we think hydrogen, but substantial progress has been made on hydrogen fuels since the.

Hydrogen, which can be made from water using renewable electricity, could be the ultimate solution for aviation if fuel handling and storage challenges can be resolved. Several companies are developing planes powered by hydrogen fuel cells for use in short- to medium-haul flights, similar to battery-powered planes. Hydrogen could also be burned in modified jet engines, a concept that Airbus is hoping to commercialize by 2035.

Hydrogen, for example, is bulky and difficult to store in large quantities. It either needs to be kept as a highly compressed gas or as a very cold liquid. To be sustainable, it has to be made in a "clean" way, from renewable sources – and supplies now are very limited. Airbus has bet big on hybrid hydrogen aircraft, announcing three futuristic ZEROe aircraft concepts, including one trippy, funhouse mirror-looking plane called the “Blended Wing Body.” The aerospace company ambitiously aims to have a mature hybrid hydrogen aircraft ready for commercial flights within the next two decades.

Myth #5: We Can Make All Planes Electric

The batteries that would be needed for long-haul flights are currently too heavy to be used, but battery-powered short-range flights have already been proven viable. Companies in the U.S. plan to produce battery-powered planes that can serve commercial flights ranging from 100-150 miles in the coming years. There are dozens of companies racing to create functional electric powered planes.

When an all-electric passenger airplane took a test flight in 2022, it didn’t have much room on board—the design, from a startup called Eviation, has space for only nine passengers. Other battery-electric planes in development are also relatively small, and studies have suggested that all-electric planes can only carry up to 19 people.

Scandinavian Airlines (more commonly known as SAS) opened bookings aboard its first electric planes—the 30-seat ES-30 model, developed in partnership with Heart Aerospace—which will take to the skies in 2028.

Dutch startup Elysian is challenging that assumption with its plans for a fully electric regional aircraft, with a range of 500 miles (805 kilometers) and space for 90 passengers, capable of reducing emissions by 90% — which it aims to fly commercially within a decade.

Myth #6: Consumers Don’t Care About Sustainable Travel

As people become more aware of climate change impacts, more are concerned about their day to day actions, and how that makes them look in front of others. In Sweden, there’s the widely publicized flygskam (flight shame), which leads some to smygflyga (flying in secret) and others to tagskryt (bragging about rail over air travel). All have been largely popularized by the “flight free” movement: a relatively small number of people who have vowed to give up flying for one year (the non-profit We Stay On The Ground has yet to reach its target of 100,000 pledges.)

An international survey from aerospace company Lilium has found that 65% of respondents believe it’s time for sustainable air travel.

The survey also found that US adults aged 18 to 34 are 2.5 times more likely to focus on sustainability when making travel decisions compared with those aged 55+.

Cost was cited as the most important factor for making travel decisions, with 54% of all respondents ranking this highest. This was closely followed by 46% of all respondents citing comfort as a factor in making travel plans, and convenience of access cited by 39%. While most electric plane companies fovus on sleek designs that will provide comfort, most will come at a higher expense.

Electric Don’t Vehicles Have to Be Expensive

When I bought my ID.4 cost was one of my biggest concerns, along with range and charging. I found a solution to my woes by leasing a car that offered free charging at Electrify America for 3 years. But that was hard to find.

I’ll save the conversation on the dysfunction of Electrify America chargers for another time. But my choice means that I save money while also not investing in a car that will be overshadowed as range expands over the next few years.

In a recent survey, more than half of Americans who don’t yet own electric cars said they were interested in buying one. But 64% said cost was a significant barrier.

As with any newer technology, electric vehicles can be expensive. But, they don’t have to be. BYD, the car brand the overtook Tesla as the largest EV seller which sells an EV that can go 250 miles on a charge for $12,000 isn’t available in the U.S.

An EV’s average price in the U.S. for 2023 was around $60,000. With U.S. interest rates at a two-decade high, the price tag for the average American car shopper is prohibitive.

Fortunately costs in the U.S. are coming down. As my former colleagues at NRDC note, EVs cost less than gas cars in the long run.

According to data from Cox Automotive (parent company of Kelley Blue Book), the average price paid for a new EV has fallen significantly—in September 2023, it came down by $14,300 over the prior year. This amounted to a cost of just $2,800 more than the average paid for a new gas-powered vehicle.

The majority of an electric vehicle’s costs come from the lithium-ion battery, and the costs of those batteries have declined 89 percent between 2008 and 2022. In addition to the advances in technology, incentives and tax credits have also greatly contributed to the downward cost trends of EVs. The other benefit is that maintenance costs are lower, with fewer moving parts.

Will Tax Credits and Incentives Help?

You can mitigate some of that cost by making use of tax incentives, which can shave thousands off an EV’s price tag. The federal EV tax credit offers up to $7,500 for new EVs and, for the first time, $4,000 for used EVs, too, for eligible buyers and EVs.

In addition, new rules from U.S. Department of the Treasury will soon allow participating auto dealers to provide the tax credit directly to consumers at the point of sale, making savings more immediate.

However, tariffs from the Biden administration make it unlikely that those cheaper Chinese EVs will be sold in the U.S. anytime soon. In parts of the developing world, where low-cost Chinese EVs are on the market, the share of electric vehicles on the road is quickly growing.

In Thailand, for example, one out of every 10 new car purchases is electric. In China, intense competition has led to more innovation. Some companies offer battery-swapping, so drivers don’t have to wait to charge their car.

Batteries keep getting smaller, lighter, and more powerful. With smaller batteries, there’s more space for storage or legroom.

Even with a federal subsidy of $7,500 towards the purchase price of an EV (made in the U.S.), many consumers still find gasoline and hybrid vehicles more affordable. For example, Toyota and Honda, who both only offer one EV each at present, both recorded substantial increases in sales in the U.S. of their hybrid vehicles, with Toyota up 16% and Honda up 32% on last year.

How Does the Charging Source Impact Cost?

If you are lucky enough to get the same Electrify America deal that I did, take it! When I go over my free 30 minute charge period, I notice the high costs of powering my car.

Charging at home is no different. Here in California, our utility, PGE keeps hiking rates, making the cost of charging higher.

Luckily EVs are 2.6 to 4.8 times more efficient at traveling a mile compared to a gasoline internal combustion engine, according to real world data collected by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

For an EV, efficiency is measured by how many kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity it consumes per 100 miles—similar to a gas-powered car’s miles-per-gallon stat. (A lower kWh/100 miles rate is better.)

A 2020 study broke down the lifetime fuel costs of battery-powered EVs versus internal combustion engine cars state by state.

EV owners in Washington State, for example, can save as much as $14,480 over the life of their vehicle—the highest margin in the country. On the other end of the spectrum is Hawaii, where going electric could ultimately cost $2,494 more over 15 years.

To get a rough estimate of your own charging costs, multiply an EV’s kilowatt-hour (kWh/100) mileage rate by your electricity rate (measured in cents per kWh), which you can find on your monthly bill. This will give you the electricity costs per 100 miles driven.

After figuring in the number of miles you typically drive in a month, you’ll be able to see how much your electric bill may go up.

So, What’s the Overall Cost?

You can figure out your savings estimate by adding together the up-front costs of your specific model (minus tax rebates) and then ongoing costs. (The DOE has created a calculator to help with this task.)

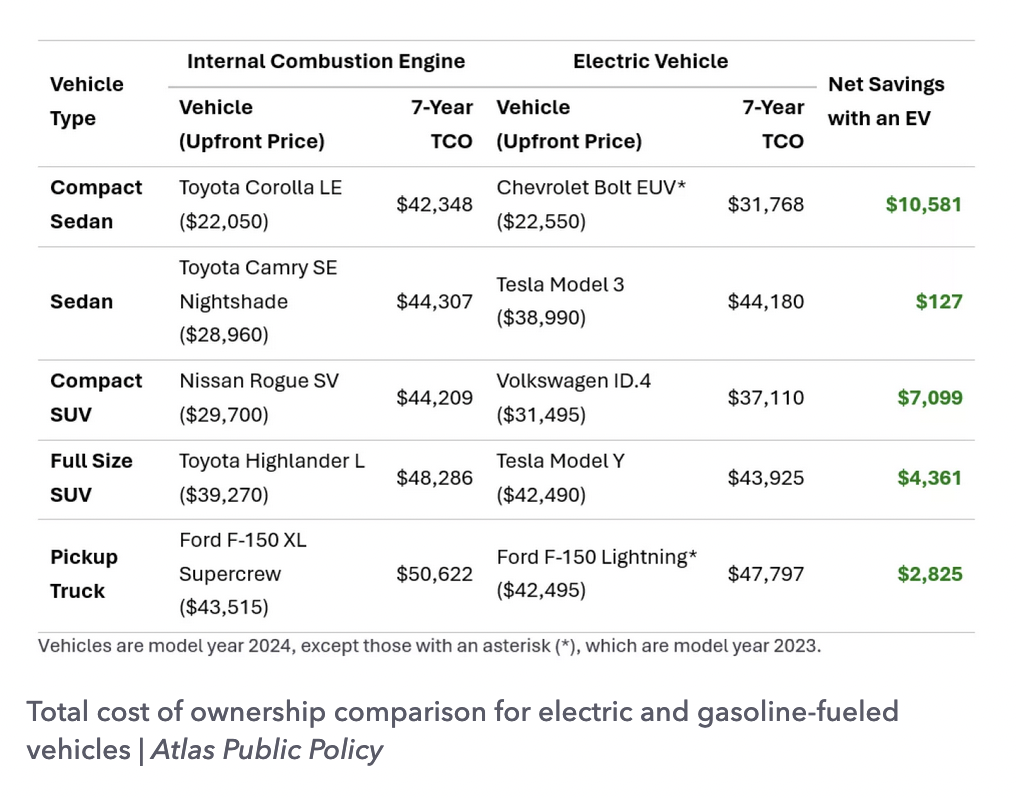

A study from Atlas Public Policy, conducted on behalf of NRDC, showed that for every major type of vehicle, owning an EV will save car owners money over a seven-year span, the average amount of time a driver keeps a new vehicle.